Read this ebook for free! No credit card needed, absolutely nothing to pay.

Words: 10105 in 4 pages

This is an ebook sharing website. You can read the uploaded ebooks for free here. No credit cards needed, nothing to pay. If you want to own a digital copy of the ebook, or want to read offline with your favorite ebook-reader, then you can choose to buy and download the ebook.

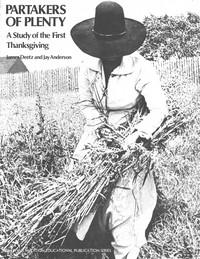

: Partakers of plenty by Anderson Jay Jay Allan Deetz James - United States Social life and customs To 1775; Thanksgiving Day History

Release date: January 5, 2024

Original publication: Plymouth, Mass: Plimoth Plantation, 1972

PARTAKERS OF PLENTY

A Study of the First Thanksgiving

James Deetz and Jay Anderson

PARTAKERS OF PLENTY A Study of the First Thanksgiving

"Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. The four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty."

So wrote Pilgrim Edward Winslow to a friend in England shortly after the colonists of New Plymouth celebrated their first successful harvest. This brief passage is the only eyewitness description of the events that were to become the basis of a uniquely American holiday: Thanksgiving. As with so many of the facts of the Pilgrims' first years in America, this occasion has become so imbued with tradition that it is difficult to place it in the perspective it occupied in Winslow's eyes. Indeed, any reference to giving thanks is notably missing from Winslow's description. What took place on that fall day some three-and-a-half centuries ago is best understood as the first harvest festival held on American soil, the acting out of an institution of great antiquity in the England the Pilgrims had left behind. It was a time of joy, celebration, and carousing, far removed from any suggestion of solemn religious concern. To appreciate just what it meant to those Englishmen, we must know who they were and what they had endured in the year prior to that first harvest of 1621.

After some preliminary explorations of the Cape, a site for a settlement was finally selected in what had been an extensive Indian cornfield some years in the past. Evidence of the Indians' former presence was everywhere. Exploring Cape Cod on foot, the Pilgrims discovered and excavated an Indian grave and entered an abandoned Indian encampment, where they found buried corn caches, some of which they appropriated. Later they would repay the Indians for the corn they had taken on that cold November day. But they had only one encounter with living Indians at that time, which was hostile and involved an exchange of shots for arrows; no one was injured in the incident. Had the Pilgrims known the situation, there would have been less concern about the Indians than they must have felt. Three years earlier the Indian population of the New England coast had been ravaged by some European disease, and as much as three-fourths of the population had perished. The Pilgrims were to have no further confrontations with the Indians until the following spring, and their next one was to be dramatically different.

As the tiny town grew, its population declined. William Bradford's account of the winter's sickness lends a sense of immediacy to what must have been a terrible time:

"So as there died some times two or three of a day in the foresaid time, that of 100 and odd persons, scarce fifty remained. And of these, in the time of most distress, there was but six or seven sound persons who to their great commendations, be it spoken, spared no pains night nor day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them. In a word, did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named...."

Just how hungry the Pilgrims were during these trying times is less clear. Provisions had been moved ashore from the ship and stored in the common house. That these were not ample for the group is suggested by numerous references in their journal to the other foods they acquired--on one occasion they killed an eagle, ate it, and said that it was remarkably like mutton. The appearance of a single herring on the shore in January raised hopes of more, but they "got but one cod; wanted small hooks," and this was eaten by the master of the ship "to his supper." In at least one case they found themselves in competition with both Indians and wild animals: "He found also a good deer killed; the savages had cut off the horns, and a wolf was eating of him; how he came there we could not conceive." But it would seem that, while food was never plentiful, actual starvation was held at bay. Yet if death was a constant companion, hunger was almost certainly a regular visitor to them.

Free books android app tbrJar TBR JAR Read Free books online gutenberg

More posts by @FreeBooks

: The missionary by Bone Jesse F Jesse Franklin Emshwiller Ed Illustrator - Science fiction; Short stories; Life on other planets Fiction; Religion Fiction; Space colonies Fiction; Psychic ability Fiction; Overpopulation Fiction